The Elephant Man

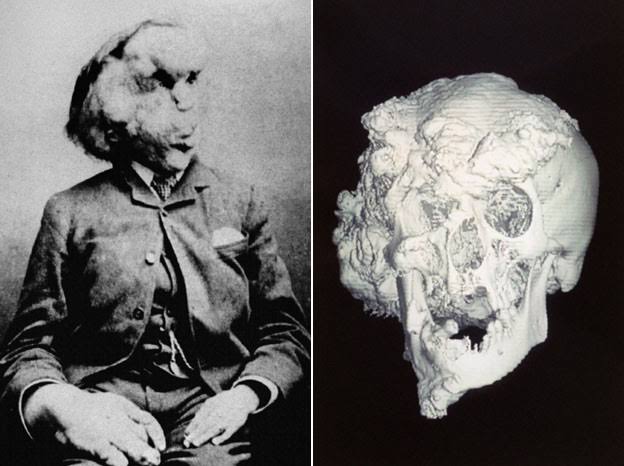

Joseph Merrick ............... The ‘Elephant Man.

Joseph Carey Merrick, a healthy baby, was born to Mary Jane and Joseph Merrick in Leicester, England on 5 August 1862. His parents associated their son's development of lumpy, greyish skin in early childhood to his mother being knocked over by a fairground elephant while she was expectant. Despite heightening physical deficiencies, including the development of a bony lump on his forehead, Joseph had a fairly usual childhood. One of his arms and both of his feet became enlarged and at some point during his childhood he fell and hurt his hip, resulting in permanent lameness. He attended school and had a close connection with his mother.

In 1873, when Merrick was just 11 years old, his mother perished of bronchial pneumonia, he would later describe her demise as the “greatest sadness in my life.” His father remarried less than a year later, and Merrick evacuated the school to seek work, ultimately finding a job rolling cigars in a factory.

But, less than two years later, his right hand had become so badly deformed that he could no longer do the job and was compelled to leave. His father, who owned a haberdashery, attained a peddler’s license for him and sent him out to the streets to peddle his shop’s wares. By this point, nonetheless, Merrick’s deformities were so severe, and his speech so inadequate as a result, that people were either scared of him or incapable to understand him and his struggles were met with minor success.

One day, after his father beat him hardly for not earning sufficient money, Merrick left to live with an uncle briefly before becoming an inhabitant at the Leicester Union Workhouse at age 17. Merrick found life in the workhouse intolerable, but incapable to find any other means of supporting himself, he was compelled to stay.

In 1884, Merrick determined to try to profit from his deficiencies and escape life in the workhouse. He contacted Sam Torr, the owner of a Leicester music hall called the Gaiety Palace of Varieties, and they devised a strategy to ensure him a spot in a human oddities show. Merrick was soon exhibited as “The Elephant Man, Half-Man, Half-Elephant” to great success in Leicester and Nottingham before finally travelling to London that November. He wore a cape and veil to hide his deformities in public but was frequently harassed by mobs as he travelled. In London, the Elephant Man display was housed across the street from the London Hospital and was continually visited by medical students and doctors curious in Merrick’s condition.

Merrick was ultimately invited by a surgeon named Frederick Treves to visit the hospital to be assessed. The results of Treves’ examination showed that, by that point, Merrick’s deformities had become extreme. His head measured 36 inches in circumference and his right hand 12 inches at the wrist. His body was covered with tumours, and his legs and hip were so deformed that he had to walk with a cane. He was found to be in otherwise decent health.

Treves presented Merrick to the Pathological Society of London in December of that year and asked Merrick to visit the hospital for additional examination. But Merrick denied, later recalling that the experience made him feel like “an animal in a cattle market.”

By 1885, a distaste for freak shows had developed in Britain and Merrick and his managers decided to try to move The Elephant Man exhibit to Belgium. The show met with only modest success, however, and Merrick’s manager there eventually robbed him of his life savings and abandoned him. After finding passage on a ship back to England in June of 1886, Merrick was mobbed by a crowd at Liverpool Street Station in London and taken into detention by the police. Incapable to understand Merrick, they eventually found Frederick Treves’ business card on him and took him to the London Hospital. Treves examined Merrick at the hospital and discovered that his condition had severely worsened in the previous two years.

By this time, Merrick was greatly disfigured, with bony protrusions and soft-tissue swellings covering much of his body. He also experienced physical and psychological pain. To avoid the stares and scrutiny of others, he covered himself in a cape and veil whenever he ventured outside. Discomforted by the reaction of others to his body, Merrick frequently quoted a poem by the hymn writer Isaac Watts: ‘Tis true, my form is something odd, But blaming me is blaming God.’

However, the hospital was deemed unable to care for “incurables” such as him, and it appeared that Merrick would be forced to watch over for himself yet again. When the chairman of the London Hospital, Carr Gromm, was unable to find another hospital to care for Merrick, he decided to publish a letter in The Times describing Merrick’s case and asking for help. Gromm’s letter resulted in a sympathetic public outpouring and enough financial donations to provide Merrick with a home for the rest of his life, and in 1887, several rooms in the London Hospital were converted to living quarters for him. Merrick’s notoriety also resulted in his being supported by members of the British upper class, most notably the actress Madge Kendal and Alexandra the Princess of Wales. (Future accounts of Merrick's life depict him and Kendal interacting in person and having a deep rapport, though it's believed that this was possibly never the case. The actress' husband, nonetheless, did visit Merrick, while Kendal herself helped raise money for Merrick's care and sent him several gifts.)

Merrick was able to visit the theatre on at least one occasion and made trips to the countryside several times over the next few years. When he was at home, he spent his time conversing with Treves (one of the few people who could understand him) or writing prose and poetry. With the help of nursing staff, he also built an elaborate cardboard cathedral, which he sent to Madge Kendal and which would later be exhibited at the hospital.

Despite Merrick’s newfound support structure, his situation, however, continued to deteriorate during his time at the London Hospital.

Joseph Merrick died unexpectedly on 11 April 1890, aged 27. Due to the size of his head, he had for his whole life slept sitting up, with his head laying against his knees. The official cause of demise was asphyxiation due to his head crushing his windpipe, although Treves, who dissected the body, said that Merrick had perished of a dislocated neck. He believed that Merrick, who had to sleep sitting up because of the weight of his head, had been attempting to sleep lying down, to "be like other people" and surmised that he died from a crushed or severed spinal cord after his head fell back due to positioning on the bed.

Treves arranged for casts to be made of Merrick's body. He also took skin samples and possibly oversaw the bleaching and mounting of his skeleton. Merrick is now thought to have endured from Proteus syndrome. His life has been the subject of several plays, films and books, which focus on his intelligence and sensitivity as a message of tolerance.

My First News Item

My First News Item My Nine News Item

My Nine News Item