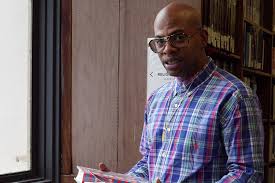

An African American Man Wrongfully Convicted Of A Murder Committed In 1991

In 1991, a detective framed John Bunn, then 14 years old, for the murder and attempted murder of two correctional officials in Brooklyn. He was sentenced to 27 years in prison after a one-day trial. He did not receive an education during his sentence.

Bunn was exonerated in 2018 with the support of The Exoneration Initiative, a non-profit dedicated to releasing those who have been unfairly imprisoned.

This man squandered 27 years of his life in prison for a crime he didn't commit.

The detention

Bunn began his ordeal on August 14, 1991, in the kitchen of his mother's apartment in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

Bunn, 14, was set for a regular day of playing ball and showing his legendary back flips in and around the four-block radius between his mother's flat on Ralph Street and the property on St Marks Avenue (his grandma). Those four blocks were his entire universe, nestled between the love of the two ladies who raised him.

Then there was a knock on the door. It had to be the cops.

Bunn recounts nearly three decades later, sitting in the same little apartment decorated with family photos, "They wanted to take me down to the police station for questioning."

He was transported to the 77th Precinct in Brooklyn, put in a cell, and shackled to a pole.

"A detective by the name of Louis Scarcella led the interrogation. And he was threatening me, telling me that if I didn't tell him what he wanted to know, I'd never see my family again. He also told me that they had already beaten up my co-defendant, slammed his head against a wall, and had him," he says.

What about the co-defendant? Rosean Hargrave, a 17-year-old Brooklyn teen. Bunn had known Hargrave "from the block," despite the fact that the two had never been more than acquaintances. But, as he soon discovered, they were both suspected of the same crime: the murder of Rolando Neischer, an off-duty Rikers Island prison officer.

Bunn remembers, "I kept assuring them, "No, I didn't have any knowledge of anything."

Detective Scarcella, who worked for years in the Brooklyn North homicide section before retiring in 1999, informed the young John that he didn't believe him.

Bunn's eyes well up with emotions as he recalls being placed in a police lineup with "big men."

The evening of the murders

Two off-duty Rikers Island correction officers and old friends, Rolando Neischer and Robert Crosson, were sitting in a car outside the Kingsborough projects, a housing project in Crown Heights, the day before Bunn was arrested. It was around 4 a.m. at the time.

Two men on bicycles suddenly approached the car, brandished pistols, and ordered the couple out. At trial, Crosson described how a gun "went off," with the bullet ripping through his hand. He was able to exit the vehicle and sprint away, losing sight of his friend.

Neischer had taken up his own weapon and fought back at some point.

Neischer was shot five times in the ensuing gunfight before the attackers jumped in the car and drove away. He was discovered 192 feet from where the car had been parked, slumped against a fence, bleeding but still alive.

They arrived for John Bunn the next day, with Crosson recognizing him and Hargrave in police lineups. Neischer succumbed to his wounds three days later.

Bunn had no idea what was in store for him the night Neischer and Crosson were kidnapped. His mother, on the other hand, had a foreboding.

Maureen Bunn awoke from a deep slumber at 4:30 a.m. to the sound of gunfire. They sounded like they were coming from her apartment complex's garden in Kingsborough.

"I thought, oh my god, I hope everyone's okay," she says, 27 years later, recounting the experience.

She padded to her children's room instinctively, looking into the darkness to check on them.

The trial has begun.

Bunn was charged with robbery and murder on August 17th. He was transported to the Bronx's notorious Spofford Juvenile Detention Center, a vermin-infested concrete structure that was shut down in 2011 following charges of assault and mistreatment. He waited there for 16 months.

"A 2005 photo of the Bridges Juvenile Center, where John Bunn spent nearly a year and a half awaiting trial."

Bunn describes Spofford as "one of the most dangerous locations I've ever been." "The employees were quite abusive. It reminded me of gladiator school. Three or four times a day, you had to battle."

Furthermore, because he had been accused with the murder of a prison officer, he had "a target" on his back. As he awaited his trial, months passed. His 15th birthday passed him by. Bunn, who was becoming increasingly unhappy and afraid, kept quiet about it.

"Things like birthdays ceased to exist for me," he explains. "In there, time slowed down."

Bunn and his mother remained optimistic that the trial would prove he was not Neischer's murderer. Crosson, the only witness to the crime, described the carjackers as light-skinned individuals in their 20s, among other things. John was a dark-skinned adolescent with a small physique.

Bunn and Hargrave were tried in November 1992, on the eve of Thanksgiving. Only four persons testified on the day of the trial: the first police officer on the scene, the medical examiner, a 77th precinct detective, and Crosson, the lone major witness who had picked both boys out of lineups.

The trial was only one day long. Both Bunn and Hargrave were convicted.

"The truth did not triumph, it did not emerge... My side of the story was also never told. I was never given the opportunity to speak up. Bunn recalls, "I never got a chance to say anything."

Bunn was originally sentenced to 20 years to life in prison, but his sentence was later reduced to nine years to life after his lawyers successfully claimed that he had been charged as an adult when he was not. Hargrave was sentenced to 30 years to life in prison.

Maureen Bunn had to be transported to the hospital after she heard the word "life."

Bunn and Hargrave both filed appeals, but they were both denied.

Imprisonment

Following a guilty verdict. Bunn was sent to a child facility in upstate New York right away. As the family expenses and eviction notices piled up, Maureen visited as much as she could, spending all of her money on long bus excursions upstate.

But John was both physically and mentally secluded. He had kept a secret for a long time. He'd never been taught how to read or write.

Bunn started with dictionaries and children's books, working with teachers on how to sound words out, letter by letter, so he could write letters to his mother. It was humiliating at first, but he quickly learnt. "It did something for my self-esteem and my imagination," he adds, as he got the hang of it.

Bunn got his GED and was reading all he could get his hands on from the prison library by the time he was 17. But reaching the age of 17 brought with it a more sobering realization: he would soon be eligible for transfer to an adult facility.

Bunn stopped a prison counselor from being raped and assaulted by another convict in 2006. His bravery played a role in the parole board's decision to let him out that year.

Bunn left Elmira wearing a shirt, shorts, and Timberland boots that his family had purchased for him, as well as his $40 in "gate money" received from his $7.50 a week jail income.

"My brother and cousin were waiting for me in the foyer when I arrived. "I felt protected once I got to them," he says. "It was the first time in 17 years that I felt safe again."

Exoneration

Bunn, however, struggled once he was released from prison. He couldn't find work because of his criminal record as a convicted murderer. He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and was granted social security and disability benefits.

After dealing with melancholy, he failed to show up for a parole hearing in 2008 and was returned to prison. He was incarcerated for another year before being freed in 2009.

A breakthrough occurred in April of 2014. Rosean Hargrave's legal team has filed a new motion to dismiss the charges.

"Scarcella's pattern and practice, which demonstrate a contempt for norms, law, and the truth, weakens our judicial system and calls for a further examination of the evidence," Justice ShawnDya Simpson, the case's judge, declared.

Rosean Hargrave's convictions were overturned by Judge Simpson, who ordered a fresh trial. Hargrave was released on bond pending a retrial after serving 24 years in jail.

A year later, after the Exoneration Initiative filed a similar motion on John Bunn's behalf, he had his own day in court. Judge Simpson criticized Scarcella's "disregard for norms, law, and truth" in her judgement, calling the evidence used to condemn Bunn "paltry."

After 27 years of unjust convictions, the District Attorney's office announced in May 2018 that Rosean Hargrave and John Bunn will not be retried. They became the 12th and 13th men to be acquitted of charges stemming from Detective Louis Scarcella's investigations. .

Bunn addressed the courtroom after Judge Simpson declared him free.

"Your Honor, I am an innocent guy, and I have always been an innocent man," he said.

My First News Item

My First News Item My Nine News Item

My Nine News Item