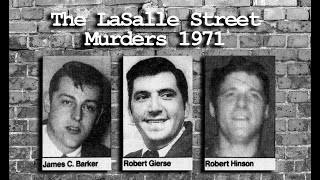

Unsolved Murder Case Of Hinson And Gierse

The Crime

In the afternoon of December 1st, 1971, the bodies of Robert Gierse, 34, Robert Hinson, 27, and James Barker, 27, were found in the home Gierse and Hinson shared at 1318 North LaSalle Street in Indianapolis1. Each man had been struck in the head, tied up with strips of sheets, and had their throats slit. Gierse and Hinson were found in their respective bedrooms; Barker was found in the bathroom.

Two of the men’s throats had been cut so violently that they were nearly decapitated. There were no signs of an effort, although Hinson, who seemed to have escaped his bindings at some point, had been hit in the head a second time. The killer had left a bloody bootprint in the bathroom, and witnesses reported seeing a yellow Oldsmobile with plates from Gibson County, Indiana parked in front of the house the night before. No weapons were found at the scene.

The Victims

To call them “colorful” wouldn’t do them justice. All three worked in the microfilm industry, which at that time could still rake in big money. Barker worked at a large outfit, Bell and Howell. He had his place nearby but spent much of his time at the house on LaSalle Street where his friends lived.

Gierse and Hinson had worked together at Records Security, a company in Jasper, Indiana owned by a man named Ted Uland. They had recently made the move to Indianapolis to start their own business, B&B Microfilm Services.

Those who knew them have said that they were hard workers, who often stayed late into the night at the office to finish up valuable jobs. But no new business can succeed through work ethic alone, and there were allegations that they’d taken some of their earlier boss’s clients, equipment, and money with them when they left. It was also rumored that they had ties to local mobsters, from whom they had bought the more stolen devices.

If they had a reputation for working hard, they had a reputation for partying harder. The three men often went out to local dive bars, where they drank heavily, got into fights, and picked up women. The Friday before their deaths Hinson had gotten into (and reportedly won) a fight over a dancer at a go-go bar. Along with their bodies, police would discover a scoreboard of their sexual conquests—the winner at the end of the year was to get a steak dinner. Barker was in the lead at 25, but their entries for November hadn’t yet been added.

The Investigation

While the police had little in the way of physical evidence, they had a prevalence of suspects. There were the husbands and boyfriends of women the three had bedded, men they had brawled with at bars, the local gangsters they had done business with, and, first and foremost, Ted Uland.

The timeline they organized went like this: On Tuesday, November 30th, Geiser, and Hinson had worked late. Their secretary said she had gone home at 5:15, and they’d told her they expected to be there until 7:30 or 8 p.m. Ted Uland had called their office twice, claiming he’d spoken to Hinson around 9 p.m. and Gierse around 9:30 p.m. about business matters. Their work number was set up to ring both in their office and their house, and Uland said he hadn’t asked which location they were at when he spoke with them. Diane Horton, a girlfriend of Gierse’s, had gone to their house at 1 in the morning and found their cars in the driveway, but left when they didn’t answer the door. The next time anyone would see them was early the following afternoon, when a business associate went looking for them at home and discovered the bodies.

After hundreds of interviews, investigators felt certain that Uland was their man. He was having financial troubles he was always having financial troubles—but he also had a key to their house, and a $150,000 life insurance policy on his former employees, which was due to expire ten days after the murders occurred. The only problem was that Uland had a solid alibi placing him at his home in Jasper, just over two hours away from Indianapolis, on the night the men were murdered. The police speculated that he had hired someone to do the job for him, but who?

With no further information and no confessions forthcoming, the case went cold.

The Reporter

In 1991, Carol Schultz, an occasional correspondent for the Indianapolis News, wrote an article about the murders for their 20th anniversary. Schultz had dealt mainly in home-and-garden tales before this, but she soon became obsessed with the case.

Her dogged search for sources led her to Carroll Horton, the ex-husband of Diane Horton, who had been involved with Gierse at the time of his death2. Carroll was a former Indy 500 mechanic, and he pointed her towards another mechanic he’d known—Floyd Chastain, who by the time Schultz contacted him in 1992, was serving a prison sentence in Florida for killing. To her great surprise, Chastain indicated her right back at Carroll. He claimed that the two of them, plus three other men, had killed Gierse, Hinson, and Barker.

Schultz brought this data to Indianapolis police, who not only found it valid but involved her heavily in their investigation into Horton. The district attorney’s office found the story less credible, and the case stalled again until 1996 when Carroll Horton and Floyd Chastain were brought before a grand jury and indicted.

The witnesses for the trial suffered from credibility problems, however. Chastain kept changing his story, at one point claiming that Richard Nixon had ordered Jimmy Hoffa to carry out a hit on the men because they had involving microfilm on him. He further declared that he was in love with Schultz, and hoped to marry her.

Schultz, for her part, had accepted a movie deal that promised to pay out $150,000 if Carroll Horton and Chastain were convicted. She had had access to police files before speaking with Chastain, and the judge alleged that she had fed him privileged information to bolster a false confession. Also, she had told Chastain that she loved him, too, but only “as a Christian.”

Eventually, a letter Chastain had written to Carroll Horton was discovered. The letter confessed for fingering him for a crime neither of them had committed and explained Chastain had wanted to be transferred to a prison in Indianapolis to be closer to family.

The case was dropped.

The Letter

In 2000, a woman in Gibson County, Indiana, found a sealed letter while searching through her late father’s safety deposit box. In the letter, her father, a man named Fred Harbison, admitted to the murders of Gierse, Barker, and Hinson.

Harbison had worked for Ted Uland in the 70s and claimed Uland had asked him to kill Gierse and Hinson in exchange for part of the insurance payout. He wrote that he had slit their throats while they were in bed, and had been forced to kill Barker as well when he came unexpectedly.

He clarified that the yellow Oldsmobile witnesses had seen was his yellow Plymouth Roadrunner. Knowing the police might be able to match the footprints at the scene to him, he’d buried the boots he’d worn that night—a detail his wife recalled him mentioning to her, although it looks like she had no idea he’d been involved in a triple homicide.

Police found his letter credible, although there’s no way to verify most of its contents. Harbison had died in 1999, and Uland in 1992.

Ironically, Uland never paid him the money he had promised.

My First News Item

My First News Item My Nine News Item

My Nine News Item